We begin shaping our experiences into narratives that make sense of the world around us from the moment we begin speaking. The stories we tell ourselves about our struggles, triumphs, and transformations do more than just communicate who we are; they define us. They shape our identity, influence our decisions, and determine how we navigate the systems we live within.

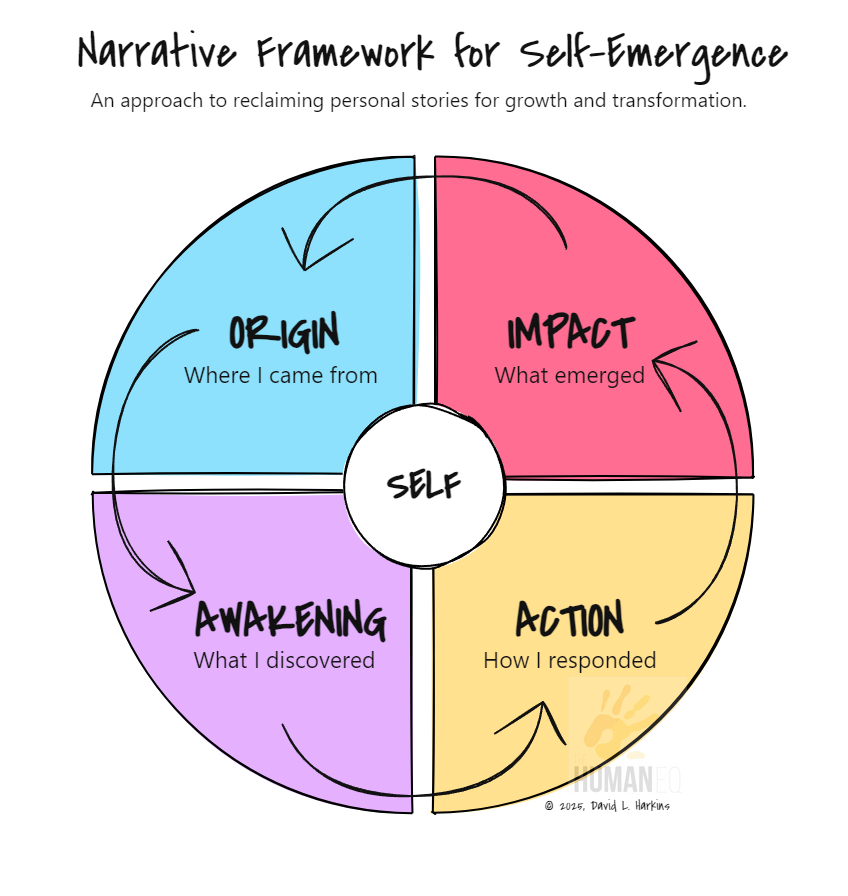

I believe our personal narratives typically unfold in four distinct phases: Origin, Awakening, Action, and Impact. Origin stories explain where we came from and what shaped us. Awakening stories capture moments of realization that shift our understanding of self. Action stories describe how we responded to these insights. Impact stories reveal the resulting transformations in our lives.

These narratives don’t emerge in isolation. They're profoundly shaped by the systems we inhabit. Our interpretations of past experiences, present understanding, and future visions absorb cultural scripts, societal expectations, and collective histories. The stories our families, communities, and cultures tell about who we should become mold our internal dialogue, often reinforcing systemic messages about race, gender, success, and failure.

While these narrative patterns feel natural, we can also change them if we choose. Unfortunately, many of us become trapped in endlessly retelling our origin stories, never progressing through the complete narrative cycle of our stories. Recognizing the embeddedness of our personal stories in the larger systems is the first step toward reclaiming these stories as tools for self-awareness, growth, and transformation.

Taking action to reclaim our narratives is critical because stories seem to influence everything from mental health outcomes to resilience in the face of adversity[i]. By consciously shaping the narratives we tell ourselves, we do more than make sense of our past, we can create a foundation for our future actions, relationships, and beliefs.

Narratives as identity builders

Psychologists and sociologists have long argued that identity is not a fixed entity, but an evolving construction shaped by our interactions with the world. Narrative Identity Theory suggests that we form our identities by crafting life stories that integrate our past, present, and anticipated future into a coherent whole [ii]. These personal narratives are not just reflections of experience, they actively shape our sense of self and our ‘possible selves’ or the versions of who we might become that guide our aspirations and fears.

For instance, consider two people who have experienced career setbacks. One person might frame the experience as a failure, reinforcing a narrative of inadequacy and feelings of powerlessness. Another might view the same experience as a turning point or a catalyst for change and growth. This can also occur in our families, too. Have you ever been sibling whose recollection of situation you were both in is completely different than yours? The facts of these situations remain the same, but how each person experiences them, and then the story they tell themselves about the experiences, determines how they perceive themselves and their future.

What we choose to include in our narratives matters. Some research suggests that when we frame their life stories with themes of redemption, specifically where challenges lead to growth and meaning, we tend to experience higher well-being and resilience[iii]. Conversely, if we construct contamination narratives, where negative experiences overshadow positive ones, we may struggle with self-doubt. Our narratives, therefore, do not simply document our experiences; they seem to shape our emotional and psychological well-being in fundamental ways.

The social construction of our stories

Even as our personal narratives feel deeply individual, they are shaped by the cultural and social systems we inhabit. Social construction theory teaches us that much of what we take for granted as 'just the way things are' is, in fact, a product of collective agreements and societal norms[iv]. The same is true for our personal stories.

Our family, faith, and society systems provide us with ready-made scripts about what constitutes success, failure, love, and belonging. These scripts shape the way we interpret our experiences. In many Western cultures, our dominant narratives around work and success are mostly stories that emphasize individual achievement, productivity, and financial gain. If we internalize these narratives, we may struggle with feelings of inadequacy if they pursue a less conventional career path, even if that path aligns with their passions and values.

Similarly, family systems influence our personal stories. If a family reinforces the idea that vulnerability is a weakness, its members may construct narratives that downplay their struggles or frame emotional needs as personal failures[v]. As Brené Brown’s research has consistently demonstrated, these inherited narratives around vulnerability and shame profoundly impact our ability to form authentic connections and develop resilience[vi]. The stories we inherit from our families often become the scripts we follow throughout life, sometimes without question. As I have written before, the work of reflection then becomes essential in identifying these narratives and determining which serve us and which may be limiting our growth.

Rewriting our narratives

I believe an Origin, Awakening, Action, and Impact framework offers a powerful lens for reflecting on, understanding and reshaping our personal stories. This framework builds upon several narrative structures that have shaped our understanding of stories across disciplines. Among these structures are Joseph Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey,” which outlines a structure where heroes depart from the ordinary world, undergo transformation through trials, and return changed[vii]. Similarly, Aristotle’s three-act structure (beginning, middle, end) offers the foundation for dramatic storytelling[viii]. In business, Simon Sinek’s book, Start With Why, emphasizes the importance of origin and purpose in creating compelling organizational narratives[ix]. In the field of Organization Development, change narratives recognize the importance of articulating a clear path from present challenges to future possibilities, similar to our Action and Impact phases[x].

What distinguishes this framework is its recognition that personal narratives often begin with origins but require movement through awakening, action, and impact to foster growth and transformation. While classic narrative structures like Campbell's focus on the transformative journey, they sometimes underestimate how easily people become trapped in their origin stories and make little, or no change at all.

We may cling to narratives about our past, whether tales of hardship that justify inaction or stories of privilege that constrain exploration, without moving toward awakening and change.

Many of us do get stuck in our origin stories, repeatedly telling and retelling where we came from without moving through the complete narrative cycle. Origins are important because they ground us in our history and context, but fixating solely on them can prevent us from embracing change and growth. When we become overly attached to our origin stories, we may unconsciously resist awakening moments that challenge these foundational narratives.

Using the Narrative Framework above, we can shift from being passive recipients of our circumstances to active agents of our transformation. We recognize our challenges not as dead ends but as pivotal moments in an evolving narrative that we have the power to shape and direct toward meaningful impact. In doing so, we gain the power to frame past struggles as part of a larger arc of growth and change rather than as fixed limitations. We can open the door to transformation and self-determination by viewing our lives as evolving narratives.

It is important to recognize the cyclical nature of this framework. We may experience multiple awakenings throughout our lives, each triggering new actions and impacts. These, in turn, become part of our evolving origin story. However, the risk of becoming trapped in origin stories remains constant. We may cling to narratives about our past, whether tales of hardship that justify inaction or stories of privilege that constrain exploration, without moving toward awakening and change.

A separate workbook for paid subscribers will be available soon to offer a deeper exploration of how to rewrite these narratives. The workbook will contain structured exercises and reflections to help guide readers through the process.

It’s worth examining how our stories serve us: Do they expand or limit our potential? Are we stuck retelling our origins without progressing toward awakening and transformation? By revisiting how we frame our personal narratives, we can identify where we've become trapped in old patterns and where opportunities exist to create new meaning. This isn’t about erasing the past but consciously choosing how we interpret and use it to move forward.

The role of personal narrative in systemic change

As we rewrite our personal narratives, we also gain the ability to tell new stories about the systems we are part of. When we reclaim our own narratives, we challenge the broader cultural stories that uphold limiting beliefs, biases, and inequalities. Consider the shifts in cultural narratives around gender roles, racial identity, and mental health in recent years. Each has been influenced by people sharing their personal stories in ways that challenge outdated societal norms[xi]. As Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie shares in her TED Talk, there is "danger in a single story" when we allow dominant narratives to define entire groups of people or experiences, we risk perpetuating harmful stereotypes and limiting human potential[xii].

Throughout history, systemic change has been catalyzed by stories that made abstract injustices tangible. The civil rights movement, the #MeToo movement, Black Lives Matter, and LGBTQ+ advocacy efforts have all been fueled by deeply personal accounts that revealed patterns of oppression and exclusion[xiii]. When enough individual narratives converge, they form a counter-narrative that challenges dominant power structures and demands reform.

Organizations, too, are shaped by the stories they tell. Workplace cultures are often reinforced by dominant narratives about what it takes to succeed, what is valued, and who belongs. By challenging and rewriting these narratives, leaders and employees can transform organizational cultures into spaces that are more inclusive, equitable, and humane[xiv]. Amy Edmondson's research on psychological safety demonstrates how organizational narratives that value vulnerability and learning from failure create environments where innovation and authentic collaboration can flourish[xv]. Recognizing the impact of narrative in these settings allows us to examine workplace norms critically, question the stories that justify exclusion, and amplify voices that have been historically marginalized.

Media and literature also play a crucial role in shaping societal narratives. The way news stories are framed, the characters represented in films and books, and the histories taught in schools all contribute to the broader social fabric. By engaging critically with these narratives and supporting diverse voices, we can ensure that our collective story reflects a more just and inclusive reality.

If narratives shape both individuals and systems, then rewriting our collective stories becomes an act of power. By elevating voices that have been silenced, questioning long-held assumptions, and fostering new ways of imagining the future, we can move beyond inherited scripts and create more equitable and inclusive societies.

The question then becomes: How will we choose to use our stories to reshape the world around us?

Reflections on the Journey

I realize how the stories I carried with me often dictated my choices and perceptions. For years, I found myself repeating the same origin stories about my family background, early career struggles, and formative relationships without recognizing how this fixation was keeping me from fully embracing new awakenings. I have held onto narratives that no longer reflected who I was becoming, strapping myself to outdated roles and limitations. Yet, in moments of deep reflection, I remembered those stories were not rigid; they evolved as I do. By questioning and reshaping my own narrative, moving beyond origins to embrace awakening, action, and impact, I found a path toward greater self-awareness and possibility.

The questions I often ask myself are:

What stories have you been telling yourself about who you are and what you are capable of?

Which of these stories serve you, and which hold you back?

How might you begin rewriting a story that empowers you to step into a fuller version of yourself?

The power of personal narratives lies in their ability to shape not just our individual lives but the systems we navigate. When we become conscious of the stories we tell, we reclaim our agency in our own lives and the broader world. In that process, we do more than rewrite our past, I believe we create new possibilities for the future.

Peace,

David

P. S. I’ve developed a workbook based on my work and experiences that I will make available soon to paid subscribers. The workbook explores how to rewrite these narratives more deeply, guiding you through the process with structured exercises and reflections. Watch your email.

[i] Dan P. McAdams, The Redemptive Self: Stories Americans Live By, Revised and Expanded (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[ii] Jerome Seymour Bruner, Acts of Meaning: Four Lectures on Mind and Culture (The Jerusalem-Harvard Lectures) (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990).

[iii] McAdams, The Redemptive Self: Stories Americans Live By.

[iv] Peter L Berger and Thomas Luckmann, The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge (New York: Anchor, 1967).

[v] Kenneth J. Gergen, An Invitation to Social Construction (SAGE Publications Ltd, 2015), https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473921276.

[vi] Brene Brown, Daring Greatly, Reprint (Avery, 2015).

[vii] Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, 3rd ed. (New World Library, 2008).

[viii] Aristotle, Poetics, trans. Malcom Heath (New York: Penguin Classics, 1997)

[ix] Simon Sinek, Start with Why (Portfolio, 2011)

[x] John Kotter, Leading Change, 1R ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2012)

[xi] McAdams, The Redemptive Self: Stories Americans Live By.

[xii] The Danger of a Single Story, Video (Oxford, United Kingdom, 2029), :03, https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story.

[xiii] bell hooks, Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black, 2nd ed. (Routledge, 2014);

Rosemary Clark-Parsons, “ ‘I See You, I Believe You, I Stand with You’: #MeToo and the Performance of Networked Feminist Visibility,” Feminist Media Studies 21, no. 3 (April 3, 2021): 362–80, https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2019.1628797;

Clotilde de Maricourt and Stephen R. Burrell, “#MeToo or #MenToo? Expressions of Backlash and Masculinity Politics in the #MeToo Era,” The Journal of Men’s Studies 30, no. 1 (March 1, 2022): 49–69, https://doi.org/10.1177/10608265211035794;

Zackary Okun Dunivin et al., “Black Lives Matter Protests Shift Public Discourse,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119, no. 10 (March 8, 2022): e2117320119, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2117320119;

Benjamin J. Newman, Tyler T. Reny, and Jennifer L. Merolla, “Race, Prejudice and Support for Racial Justice Countermovements: The Case of ‘Blue Lives Matter,’” Political Behavior 46, no. 3 (September 2024): 1491–1510, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-023-09881-y.

[xiv] Edgar H. Schein, Organizational Psychology, 3rd ed. (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1980)

[xv] Amy C. Edmondson, “Psychological Safety, Trust, and Learning in Organizations: A Group-Level Lens,” in Trust and Distrust in Organizations: Dilemmas and Approaches, ed. R. M. Kramer and R. S. Cook (Russell Sage Foundation, 2004), 239–72; https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-16590-010

Amy C. Edmondson, “Managing the Risk of Learning: Psychological Safety in Work Teams,” in International Handbook of Organizational Teamwork and Cooperative Working, ed. Michael A. West, Dean Tjosvold, and Ken G. Smith (Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2008), 255–75, https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470696712.ch13.