Economic shields and social shifts

The McKinley Tariff’s impact on industrial growth and the human experience.

In 2014, I wrote an essay for a macroeconomics class that focused on how the McKinley Tariff informed our positions on globalization and the tariff's impact on the U. S. economy. I revisited the essay with the recent talk of tariffs and updated it to consider systems thinking perspectives and the human equation outcome.

In the mid-nineteenth century, technological advances and improvements in the United States’ transportation infrastructure permanently altered the country's economic and social systems. The rise of industrialization, mechanized production, and national-scale distribution networks redefined labor, trade, and human livelihoods. Steamboats, railroad expansion, and the telegraph meant that people, products, and information traveled faster and farther, transforming how businesses operated and forcing them to compete beyond their local communities [i]. While these changes expanded economic opportunity, they simultaneously disrupted the existing system, displacing small business owners and independent craftsmen who struggled to adapt to a market increasingly dominated by industrial conglomerates.

It represented a fundamental reorganization of societal systems as entire communities moved from self-sufficiency to wage dependency, from land ownership to industrial labor, and from local interdependence to urban anonymity.

At the same time, the workforce itself was in transition: the emergence of factory jobs in the Northern and Midwestern cities attracted laborers from rural communities, where agriculture had historically been the backbone of economic stability [ii]. This shift was not just about economic migration, though. It represented a fundamental reorganization of societal systems as entire communities moved from self-sufficiency to wage dependency, from land ownership to industrial labor, and from local interdependence to urban anonymity.

Foreign competition further complicated the system, pushing American businesses to demand protectionist policies that would shield them from market fluctuations and international price pressures [iii]. In response, William McKinley, then a Congressman from Ohio, championed tariffs as a stabilizing force to the broader market system. Although McKinley was not an economist, his systems perspective was shaped by his background in manufacturing, where he recognized that industrial stability required shielding domestic production from foreign price undercutting [iv].

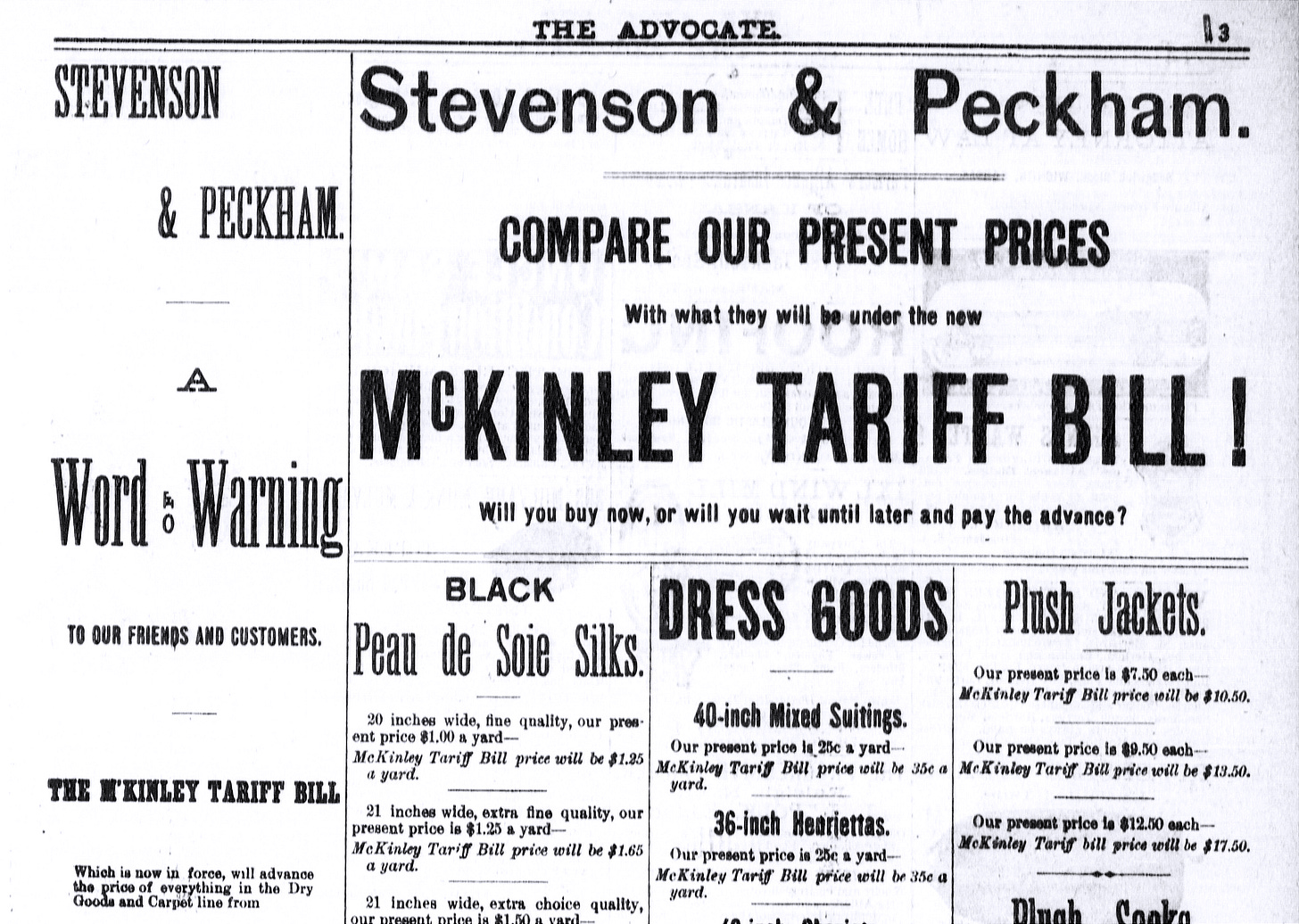

As chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, McKinley was instrumental in crafting the Tariff Act of 1890, commonly known as the McKinley Tariff, which became law on October 1, 1890. This legislation significantly raised protective tariff rates to nearly 50% on average for many American products, aiming to protect domestic industries from foreign competition [v].

Yet, systemic interventions such as the McKinley Tariff do not operate in isolation; they create cascading effects, often with unintended consequences that we today call “wicked problems” [vi].

The systemic trade-offs of the McKinley Tariff

While the McKinley Tariff strengthened specific industries, it created structural disadvantages for other parts of the economy, particularly agriculture. Small farmers, dependent on export markets, suddenly faced retaliatory tariffs from Britain and other trading partners [vii]. This policy shift highlights a key lesson in systems dynamics: interventions designed to protect one node in a system (industrial manufacturers) can create stress in other nodes (agricultural producers), leading to instability elsewhere.

For Midwestern farmers, the tariff's impact was devastating. Many relied on foreign buyers to sell surplus grain and livestock, but when international markets retaliated, they were left without customers. This economic shock rippled through rural communities, leading to financial distress, increased foreclosures, and deeper class divides between urban industrialists and rural agrarians. These systemic pressures directly contributed to the rise of populism and rural discontent, culminating in broader political instability in the following decades [viii].

This economic shock rippled through rural communities, leading to financial distress, increased foreclosures, and deeper class divides between urban industrialists and rural agrarians.

The McKinley Tariff increased consumer costs at the household level, disproportionately affecting working-class families [ix]. By making imported goods more expensive, the policy inflated prices on household staples, forcing lower-income Americans to devote more of their wages to basic necessities. From a systems perspective, this demonstrates how economic policy decisions reverberate across social structures, intensifying inequalities and reshaping everyday life.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Human Equation to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.